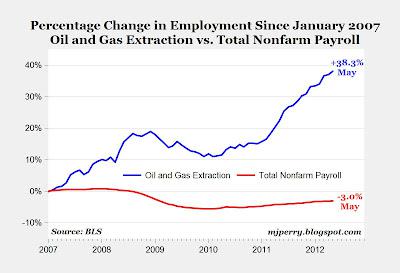

The game-changing development of shale oil and gas in the United States has motivated countries around the world to tap potentially massive resources.

187272

Shale will alter the energy security picture for major end-use markets, limiting individual producer petro-power and creating a more competitive marketplace for LNG and potentially enabling further market liberalization in Europe and elsewhere, said

Amy Myers Jaffe.

“What has changed is that now we have this huge potential of resources that are exactly where the demand centers are,” explained Jaffe, director, Energy Forum at the Baker Institute, Rice University.

“That changes not only the geopolitics of oil and gas, but also the business model that companies are going to follow.”One example of a change in geopolitics involves petrodollars. “Think about the economic impact of shipping all those dollars to Saudi Arabia. Where do they put those dollars?” she asked participants on May 23 at the seventh annual Mayer Brown conference on Global Energy: The New Frontier.

“This money comes flooding into the stock market with all of you. There’s a bubble and you lose everything you own,” she said with a laugh. “How many times has that happened -- at least four times.

“When you pay $5 at a gasoline station

, imagine if that money stays here with new jobs in Pennsylvania instead of in the Middle East. It would make a real difference to your and my quality of life just to have that money stay here. It certainly is true that it matters to have the production be here,” she emphasized.

And, that wave of U.S. production is washing over other areas in the world as well. “Even though the European

shale hasn’t been developed yet, just having U.S. shale be developed already has Gazprom on the run. You already have some gas-on-gas pricing from Russia to Europe. The market share of Russia in non-FSU Europe is falling and could be below 13% by 2040.

“It’s really changed the techno-power aspect of international dialogue, and it’s also created opportunities for IOCs and independents in terms of negotiating strength,” Jaffe said.

One more aspect of the impact in Europe is that “the ride back to liberalization is a possible natural outcome. There are lots of barriers to having that happen,” she continued. “But, we’ll be seeing a lot more liberalization on the European continent.”

Shale plays are having an impact on how countries are approaching resource development. The nationalization of YPF by the Argentine government, for example, fits in the context of huge shale resources.

Jaffe explained that Argentina was willing to privatize YPF when the government thought there were hardly any resources left in a poor, picked-over basin.

“When suddenly they realized there were billions of barrels of oil and gas equivalent in the ground, then they weren’t so enthusiastic about not having a national oil company. That’s my interpretation of why that happened,” she added.

The Baker Institute has been doing a study on estimated ultimate recovery (EURs) in shale plays around the world. “If you look at Argentina, it’s very, very attractive. There are a lot of companies down there now --

Shell,

Exxon and a few others,” she said.

Mexico is another country that could be a major shale player if the country decides to reform the sector. “They are talking about creating a new entity to do shale gas. If they do that, it would be a game-changer. I’m not saying it’s going to happen, but at least they are talking about it,” Jaffe noted.

In the Middle East and North Africa, “the Jordanians want to pursue their shale. Morocco believes they have shale. Oman is looking for shale,” she continued.

China’s shale market is expected to grow slowly and provide 15% of the domestic market. However, there are three challenges for developing China’s shale resources: 1) in many areas, there are problems with water resources; 2) there is a lack of infrastructure; and 3) some of the shale is in mountainous areas where it is not easy to drill, she explained.

In the U.S., the industry now realizes that oil is not limited to the Bakken formation. “People are developing the technology and becoming more sophisticated at it. The results we are seeing in the Eagle Ford are quite substantial,” she stated.“Some people say that by next year, we’re going to have 1.0 million barrels per day (MMb/d) of oil production onshore in the U.S. just between the

Eagle Ford and Bakken,” she said.

However, there are more oil plays than that. The list includes: Bakken in North Dakota; Permian, Avalon, Bone Springs, Wolfcamp and Eagle Ford in Texas-New Mexico; Utica in Ohio; Marcellus in Pennsylvania; Niobrara in Colorado-Wyoming; Sunniland in Florida; Tuscaloosa Marine in Louisiana; Mississippi Lime in Oklahoma; and Monterrey basin in California.“You can see it’s a pretty long list, and it’s not a Texas-Louisiana play. We have northwest Pennsylvania, Ohio, Florida and California,” she emphasized.

Total technically recoverable resources are estimated at 60 billion barrels. “If that turned out to be a correct estimate, that would support 2.0 MMb/d, and that is really world class. We’re talking about a big resource.”

The U.S. could be relatively self-sufficient by 2025. Shales could add 3.0 MMb/d. The

Gulf of Mexico could add 2.0 to 3.0 MMb/d and raising automobile standards to 54 mpg could shave off 4.0 MMb/d. “We’re talking about very low levels of imports to the U.S.”

In a reference case, the Baker Institute estimated that U.S. shale gas production will exceed 50% of total production by 2030. The strongest long-term production is in the Marcellus and Haynesville shales, followed by the Barnett, Eagle Ford and Fayetteville shales.In Canada, shale is expected to reach one-third of natural gas output by the 2030s, Jaffe said.

The institute has run computer models of liquefied natural gas exports through 2040. “We’ve run computer simulations. The computer never ships U.S. gas to Asia. Bottom line is that your project from Horn River is what gets exported. Something will be exported. Whether it is from the Gulf Coast is another question,” she continued.

Contact the author, Scott Weeden, at

sweeden@hartenergy.com.

Download the Eagle Ford Shale Impact Presentation

Download the Eagle Ford Shale Impact Presentation

.jpg)